We’re hearing a lot about the decline in new hires into the U.S. economy—statistics that sent the markets into two different one-day panics last month. But when you look at the big picture, the unemployment rate, since the start of the year, has moved only slightly from 3.7% (extremely low) to 4.2% (still on the lower end of the historical spectrum).

We’re hearing a lot about the decline in new hires into the U.S. economy—statistics that sent the markets into two different one-day panics last month. But when you look at the big picture, the unemployment rate, since the start of the year, has moved only slightly from 3.7% (extremely low) to 4.2% (still on the lower end of the historical spectrum).

This matters because most observers believe that the relative decline in new hires will force the Federal Reserve Board to make rate cuts at its upcoming meetings. Others, however, point out that the current unemployment rate hardly signals an imminent recession, and stimulus is less important than bringing down the inflation rate.

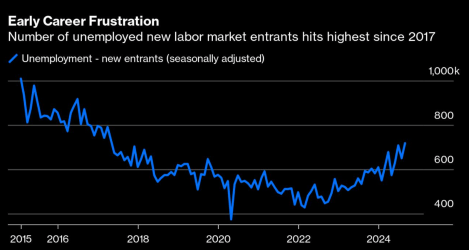

Who’s right? Looking past the aggregate numbers, the worrisome cohort is new entrants to the workforce—people graduating from high school and college, who are looking for jobs at a time when companies have put a pause on hiring. An article in Bloomberg cites Bureau of Labor Statistics research noting that 718,000 new entrants to the labor force were unemployed as of August, the most since April 2017. Add in parents who took time away to focus on kids, who want to reenter the workforce, and roughly half of the rise in the unemployment rate is people who expected to find jobs and are being turned away.

A rate cut won’t meaningfully boost stock prices; the expectation is already built into current prices. But it might lubricate the economy enough so that new workforce entrants and re-entrants will be absorbed into salaried positions.